In recent years, batik has become visually synonymous with Peranakan culture. It appears in exhibitions, home décor, fashion editorials, and heritage narratives, often framed as a hallmark of Straits Chinese identity. This visibility has brought batik renewed attention, but it has also quietly shifted the centre of gravity of its story. The deeper origins of batik, rooted in Java and shaped across the Malay world, are frequently glossed over. What was once a regional art with layered histories is at risk of being read through a single cultural lens.

Yet batik did not begin in the shophouses of the Straits Settlements, nor was it born as a hybrid aesthetic. It emerged from centuries of craft, philosophy, and ritual in Java, before travelling across seas, adapting to new lands, and being adopted by many cultures along the way.

Batik is more than a decorative textile. It is a living archive of history, belief, identity, and artistry. It began centuries ago in Southeast Asia and has since woven its way into cultures around the world. At its heart, batik is defined by a technique: the use of wax to resist dye on fabric, creating intricate patterns that emerge through repeated cycles of drawing, dyeing, and revealing. Yet behind this technique lies a rich story of human ingenuity and cultural expression.

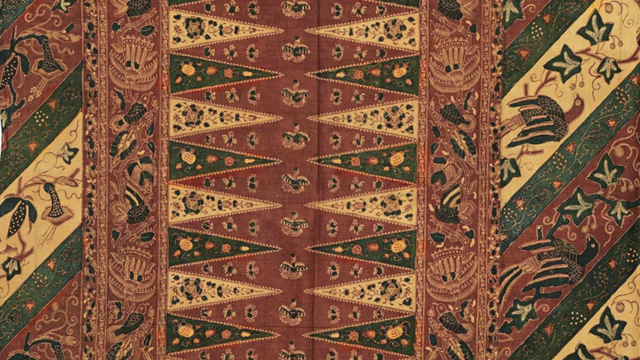

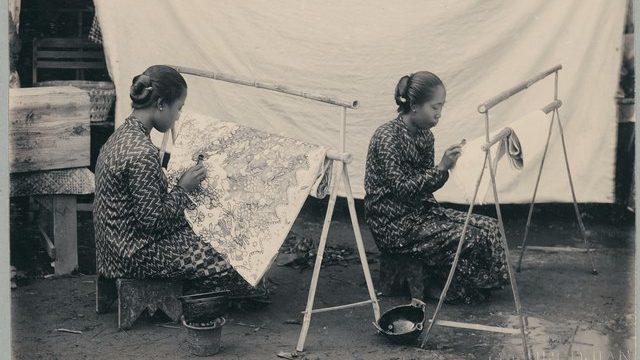

The earliest roots of batik can be traced to Java in present day Indonesia, where the craft evolved into a highly refined art form by at least the 12th century. While resist dye techniques appeared in parts of Africa, India, China, and Japan, it was in Java that batik reached extraordinary levels of complexity and symbolism. Javanese artisans developed tools such as the canting, a small copper pen used to apply molten wax by hand, and perfected methods that allowed for delicate lines, layered colours, and astonishing detail.

Batik in Java grew within royal courts and village communities alike. It became both an elite art and a domestic craft, passed from generation to generation, often from mother to daughter. Patterns were not created at random. They followed inherited codes, regional styles, and philosophical frameworks rooted in Javanese cosmology. A piece of cloth could communicate status, origin, and even moral values. In this way, batik became a visual language, one that could be read by those who understood its symbols.

In Javanese society, batik was never merely ornamental. Certain patterns were reserved for royalty. Others marked life’s milestones such as birth, marriage, and death. Motifs carried meaning. The parang symbolised power and continuity. The kawung reflected balance and cosmic order. Floral and geometric designs conveyed harmony with nature. Wearing batik was a way of situating oneself within a social and spiritual universe. Cloth became a form of quiet storytelling.

Through centuries of maritime trade across the Malay Archipelago, batik travelled beyond Java and into the Malay Peninsula. Merchants, migrants, and intermarriages carried both cloth and technique across the Straits of Malacca. As batik took root in places such as Kelantan and Terengganu, it began to reflect a different rhythm of life. While Javanese batik often featured dense, symbolic patterns and earthy tones, Malay batik evolved with freer compositions, larger floral motifs, and brighter, more expressive colours. The designs were less bound by court hierarchy and more open in spirit, shaped by coastal environments, tropical flora, and everyday scenes.

Malay batik also embraced different methods, particularly brush painting and block printing, which allowed for bolder strokes and fluid colour transitions. Where Javanese batik often layered multiple dye baths with meticulous precision, Malay batik leaned toward spontaneity and visual openness. White spaces were celebrated. Colours flowed. This was not a departure from tradition, but a regional reinterpretation, shaped by climate, lifestyle, and aesthetic sensibilities. Batik became not only ceremonial wear, but a living, wearable art woven into daily life.

During the colonial era, batik began to travel far beyond Southeast Asia. Dutch traders brought batik to Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, where it fascinated textile manufacturers and collectors. Attempts were made to replicate the wax resist effect through industrial processes, leading to the development of printed batik style fabrics. Though these could not replicate the depth and individuality of hand drawn batik, they carried its visual language into new markets and imaginations.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, batik inspired the rise of wax prints in Africa, particularly in West and Central Africa. These textiles, initially produced in Europe and modelled on Indonesian batik, were introduced to African markets and soon absorbed into local cultures. Over time, communities reinterpreted the patterns, assigning their own names, stories, and meanings to them. What began as a Southeast Asian technique became an integral part of African visual identity, shaped by local narratives, politics, and social life.

The influence of batik also reached artists and designers in Europe and the Americas. During the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements, creatives were drawn to batik’s organic lines and handcrafted ethos. Artists and textile designers experimented with batik as a medium of fine art, using it for wall hangings, tapestries, and garments. In the 1960s and 70s, batik became associated with counterculture, individuality, and a return to handmade processes, appearing in fashion, interior design, and contemporary art.

Along these cultural currents, batik also flowed into hybrid societies of Southeast Asia. Communities such as the Peranakan, shaped by centuries of interaction between Chinese and Malay worlds, adopted batik into daily life and dress, blending it naturally into their visual culture alongside other inherited traditions from the indigenous cultures.

While rooted in the same wax resist tradition, Peranakan batik differed subtly from its Javanese and Malay counterparts. It often favoured softer pastel palettes, delicate borders, and motifs drawn from Chinese symbolism such as peonies, phoenixes, and auspicious emblems, creating textiles that felt lighter, more ornamental, and distinctly domestic in character.

Today, batik stands at the crossroads of tradition and modernity. In Indonesia, it remains a national symbol and is recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In Malaysia, it continues to evolve with strong regional identities. Designers reinterpret ancientmotifs in contemporary silhouettes. Digital tools coexist with the canting. Across the world, batik is taught in art schools, used in haute couture, and adapted in cultures far removed from its birthplace.

What makes batik endure is not only its beauty, but its philosophy. It is slow art in a fast world. Each piece demands patience, precision, and intention. Every line is drawn by hand. Every layer is earned. In an age of automation and mass production, batik reminds us that meaning can be embedded in material, and that cloth can carry memory.

From royal courts in Java to coastal towns of the Malay Peninsula, from global trade routes to contemporary studios, batik’s journey is a testament to how culture travels. It does not erase origins. It invites reinterpretation and belonging. It began as wax on cloth. It became a bridge between civilisations. And it continues to prove that art, at its best, is both deeply rooted and endlessly expansive.