By someone who has spent more nights with old manuscripts than with actual people.

History has a funny temperament. In some regions, it sits comfortably and unchallenged, like a pampered cat perched atop a bookshelf. Medieval Europe is allowed to have its knights and castles without anyone demanding footnotes. The Middle East enjoys an uncontested lineage of prophets and dynasties. Even the Americas, once dismissed by colonisers, have begun reclaiming indigenous histories without being told their ancestors were imaginary.

But step into Southeast Asia, and suddenly history turns into a courtroom drama.

Speak of Austronesian expansion, and someone doubts it. Mention the deep-time presence of Austroasiatic communities, and someone questions it. Talk about the indigenous foundations of the Malay world and wider region, and the conversation becomes cautious, hedged, somehow always “in dispute”.

Here, history does not rest. It is interrogated, doubted, often dismissed.

And the irony is almost too rich: many of the loudest doubts come from communities who arrived long after the region’s earliest inhabitants had already carved riverside settlements, sailed open oceans, cultivated fields, and built networks stretching from Madagascar to Micronesia.

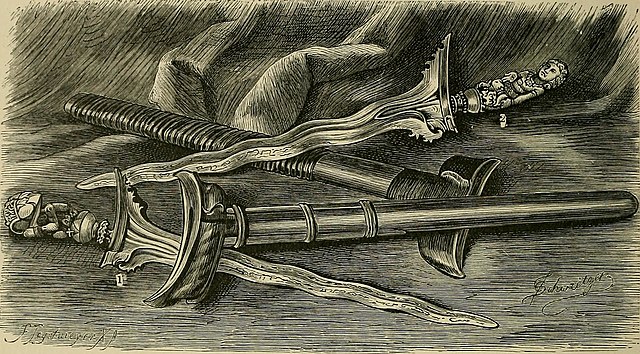

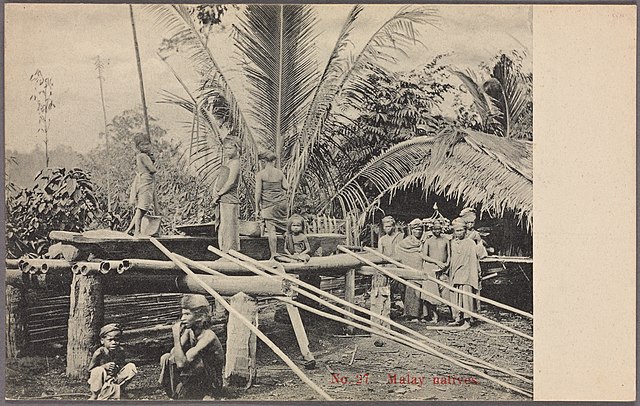

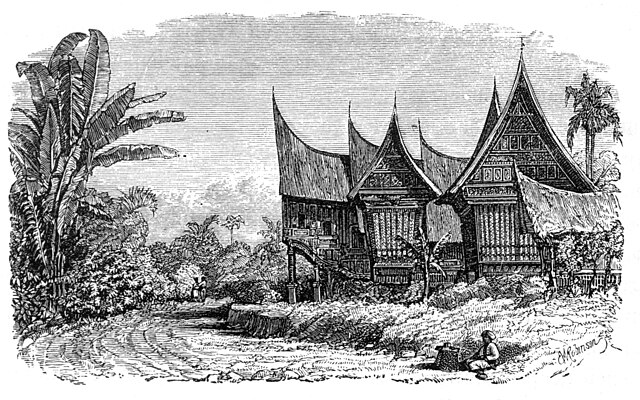

Think of the Malays, who emerged from millennia of Austronesian migration, trade, and cultural fusion. Think of the Orang Asli of the Malay Peninsula, the Dayak of Borneo, the Orang Laut who ruled the sea highways, the Bajau sea nomads, the Kadazan Dusun of Sabah, the Iban and Bidayuh of Sarawak, the Batak and Minangkabau of Sumatra, the Balinese with their layered cosmologies, the Tausug of Sulu, the Cham of mainland Southeast Asia, and the Mon and Khmer who carried forward deep Austroasiatic legacies.

These communities lived, shaped, and stewarded the region long before anyone else sailed in or arrived by caravan.

Yet their histories are the ones constantly asked to defend themselves.

No one tells the French to “prove” they descended from Gauls. No one tells Middle Eastern communities that their genealogies and oral traditions are “unscientific”. But Malays and other indigenous groups in Southeast Asia are often challenged, questioned, or spoken over when they assert stories of origin and continuity.

A Norse saga is treated as evidence. An Orang Laut oral tradition is treated as myth.

A Middle Eastern genealogy is respected. A Malay hikayat is doubted unless confirmed by foreign sources.

A Chinese imperial record describing Southeast Asia is treated as authoritative. But the living memories of the people being described are treated as secondary.

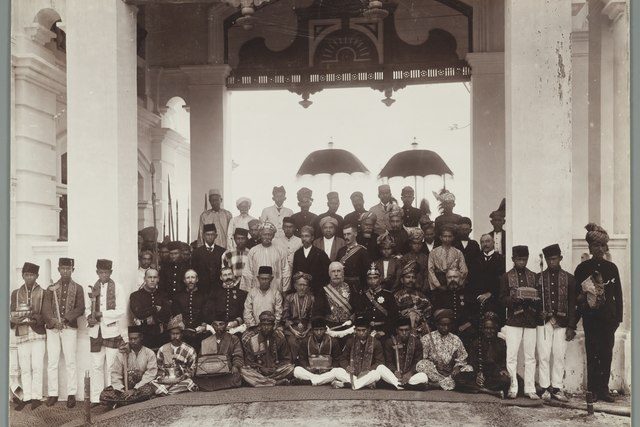

This double standard did not appear out of nowhere. It was inherited from colonial scholarship, which treated anything unwritten as primitive, anything oral as unreliable, and anything indigenous as needing external validation. Written records were king. Oral traditions were “colorful”.

This hierarchy never fully disappeared. It simply changed hands.

Today, you can see it in online discussions, where indigenous claims are subjected to intense skepticism while imported narratives pass unquestioned. You see it in school curriculums that highlight Rome, India, and China, but reduce Austroasiatic and Austronesian histories to a few scattered paragraphs. You see it when Malay history is deemed “unclear” unless referenced by outsiders, ignoring the complex intellectual traditions embedded in language, ritual, navigation, agriculture, and cosmology.

Austroasiatic peoples preserved their histories in place names, cycles of rice cultivation, ritual specialists, and kinship structures. Austronesians preserved theirs in navigation systems, genealogies, poetry, and a maritime worldview so vast it connected half the planet.

These were not accidents of memory. They were deliberate archives.

The issue is not migration. Southeast Asia has always been a crossroads of Chinese, Indian, Arab, Persian, and later European traders, scholars, and settlers. The region is richer because of these encounters.

The problem is the quiet implication that the oldest histories of this land do not count unless someone else verifies them.

The Malays, the Dayak, the Orang Asli, the Cham, the Mon, the Khmer, the Iban, the Bidayuh, the Tao people of Orchid Island, the Kadazan Dusun, the Tausug, and so many others did not build villages, kingdoms, maritime networks, and knowledge systems only to be told their ancestors are “uncertain”.

These are the foundational peoples of Southeast Asia. Everyone else arrived later and became part of the shared story. But the foundations are not up for negotiation.

The question now is not why Austronesian or Austroasiatic histories are “disputed”.

The question is why anyone ever believed they were optional.

Some histories were written in ink. Others were written in forests, rivers, saltwater, and sky.

Only one set is still fighting to be believed.