Before it was called Singapore, this island bore many names. Temasek, Pulau Ujong, and Singapura were among some of the names that were used to refer to the island. These names, found in early records and oral traditions, reflect a long and layered history that predates British colonisation by many centuries.

Yet, many today are unaware of this precolonial past. Some even dismiss or distort it, creating confusion and disconnection from the island’s true origins. Over time, this has led to a generation of Singaporeans who know little about their land’s indigenous roots.

Fortunately, documented records, archaeological discoveries, and oral traditions allow us to piece together this forgotten story, a story of thriving Malay and Javanese kingdoms, sacred hills, and a civilisation that once commanded the seas.

Let’s take a journey through time to rediscover the empires that once ruled and influenced this island long before 1819.

The Srivijaya Empire

Long before European ships arrived, the region was part of a powerful maritime civilisation– the Srivijaya Empire. Originating from Palembang in Sumatra, Srivijaya was a Malay Buddhist thalassocracy – a sea-based empire that flourished between the 7th and 11th centuries CE.

Its rulers were Malay, its language was Old Malay, and its influence stretched across Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and the islands of Southeast Asia. At its height, Srivijaya controlled key maritime chokepoints, including the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, the lifeblood of global trade between India and China.

Chinese chronicles such as the Xin Tang Shu (New History of the Tang Dynasty) mention that Srivijaya controlled ports along the Malay Peninsula, including the southern tip thus suggesting that Temasek (ancient Singapore) fell within its sphere of influence.

Later records, like Zhao Rukuo’s Zhu Fan Zhi (1225), note that Temasek was once under Srivijaya’s control before emerging as an independent port, evidence of its enduring strategic importance.

Archaeological finds in Singapore also support this connection. Excavations near Fort Canning Hill and the Singapore River uncovered Tang Dynasty ceramics, Sri Lankan and Chinese coins, and Buddhist relics, all pointing to early trade and cultural contact.

These artifacts mirror those found in Srivijayan sites across Sumatra, suggesting that Singapore was integrated into its trade network.

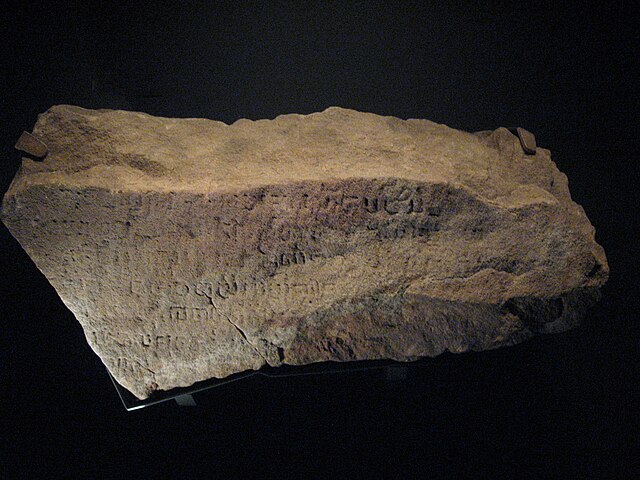

The discovery of the Singapore Stone further strengthens this link. Dated to between the 10th and 13th centuries, the stone bears inscriptions in Kawi script with Sanskrit and Old Malay elements, languages used in Srivijayan domains.

This reveals not only early literacy but also the island’s participation in the wider cultural world of Srivijaya.

Through both evidence and logic, it is clear that early Singapore was not an empty island, but an active part of the Srivijayan maritime network, home to indigenous Malay communities who traded, sailed, and interacted with civilisations from across the seas.

Sang Nila Utama: The Srivijayan Prince Who Founded Singapura

After Srivijaya’s decline in the 13th century, its influence lingered through successor states. From among its royal lineage arose Sang Nila Utama, a prince of Palembang, remembered today as the founder of Singapura.

According to the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), Sang Nila Utama descended from the line of Sang Sapurba, a divine ancestor believed to have descended upon Bukit Siguntang in Sumatra.

This sacred genealogy connects him directly to Srivijaya’s royal blood and to the broader tradition of divine Malay kingship, where rulers were seen as chosen by the heavens to govern land and sea.

Intrigued by stories of a distant island called Temasek, Sang Nila Utama set sail from Palembang to explore it. En route, his ship was caught in a violent storm.

In desperation, he threw his crown, a symbol of worldly power, into the sea, and the storm subsided. When he landed safely on Temasek’s shores, he was struck by the island’s beauty and strategic position.

There, he reportedly saw a strange, majestic creature – described as a lion. Inspired, he named the island Singapura, from the Sanskrit words simha (lion) and pura (city) –“The Lion City.” Though lions never roamed the region, the name symbolised strength, courage,and sovereignty.

Sang Nila Utama established his kingdom atop Bukit Larangan – now known as Fort Canning Hill. Archaeological findings of gold ornaments, ceramics, and beads from the 13th–14th centuries suggest that the hill was indeed a royal or ceremonial center. From,here, Singapura blossomed into a thriving port city, connecting the Malay world with traders from China, India, and the Middle East.

While the story of Sang Nila Utama may contain mythical elements, it should not be dismissed as mere legend. Across civilisations, myth and history often intertwine.

Ancient Greece had tales of Zeus and Athena shaping their world; Rome claimed descent from Aeneas, a hero of the Trojan War; and yet both were real civilisations with traceable empires, cultures, and legacies.

Similarly, the Malay world’s classical narratives – from the Sejarah Melayu to oral hikayats –use symbolic storytelling to express truths about lineage, kingship, and identity.

These myths are not fabrications but cultural vessels, carrying memories of migration, settlement, and the rise of early polities.

Thus, even as we approach these stories critically, we must also approach them respectfully, understanding that myth and memory together form the foundation of Malay history – not to be separated, but read in conversation with one another.

Chinese records from the Yuan Dynasty mention Temasek as a bustling harbor and note its conflicts with Siam, showing that it possessed its own fleet and defended its independence.

Sang Nila Utama ruled wisely and was succeeded by a line of kings who continued to strengthen Singapura’s position in the region. His descendants, Sri Wikrama Wira, Paduka Sri Rana Wikrama, and finally Sultan Iskandar Shah (Parameswara), carried on this lineage.

Sang Nila Utama’s legacy lived on not only in Singapore but in the establishment of the Malacca Sultanate by his descendant Parameswara, which would later become one of the greatest empires in Malay history. Through this lineage, we see a continuous thread of Malay sovereignty – from Srivijaya, to Singapura, to Malacca.

The Majapahit Empire and the Fall of Ancient Singapura

In the late 13th century, another maritime power began to dominate the region, the Majapahit Empire of Java. Founded in 1293 by Raden Wijaya, Majapahit expanded rapidly, controlling much of Indonesia, Sumatra, and parts of the Malay Peninsula. Like Srivijaya, Majapahit thrived by mastering the seas.

Under King Hayam Wuruk and his famed general Gajah Mada, Majapahit sought to bring all major Southeast Asian ports under its influence. The Nagarakretagama (1365) lists Temasek among Majapahit’s tributary states, confirming Singapore’s continued importance in the regional power structure.

By this time, Singapura was ruled by Sultan Iskandar Shah (Parameswara). Tensions with Majapahit escalated, and around 1390 – 1400 CE, the Javanese launched an invasion. The Sejarah Melayu recounts betrayal within the court that led to the city’s fall. The royal family fled north, eventually reaching the Malay Peninsula, where Iskandar Shah founded Malacca.

Though the fall of Singapura marked the end of one kingdom, it gave rise to another. The Malacca Sultanate became the new center of Malay civilisation – Islamic, cosmopolitan, and powerful – continuing the legacy of governance and trade that began under Sang Nila Utama’s lineage.

Archaeological evidence from Singapore, including Majapahit-style pottery and Chinese porcelain, suggests the island remained active even after its fall, likely serving as a port under Majapahit’s network.

Legacy: Remembering the Indigenous Past

The intertwined histories of Srivijaya, Singapura, Majapahit and the Malaccan Sultanate show that Singapore’s story did not begin in 1819. For over a millennium, it was part of a vibrant Malay world.

This was a world of kings,seafarers, warriors, and traders who shaped the economic and cultural destiny of Southeast Asia.

This history challenges narratives that portray the island as “empty” or “undeveloped.” In truth, Singapore was already a sophisticated port city within a network of indigenous empires, a crossroads of faith, commerce, and ideas.

Recognising this past is vital. It reclaims Singapore’s place within the continuum of Malay and Austronesian civilisation and reminds us that the island’s story is one of continuity, resilience, and identity – not of sudden creation, but of deep, enduring roots.

Today, the traces of these kingdoms may lie buried beneath glass towers and highways, but they live on in the stories, language, and spirit of the Malays – the island’s first custodians.

To remember them is to remember that Singapore’s roots run deep, across seas and centuries, bound by the same Austronesian tides that shaped a shared civilisation.